The Earliest 'Trials' Production First Pattern F-S Fighting Knife

An Analysis Of The Earliest Production Of Wilkinsons First Pattern Fairbairn-Sykes Fighting Knife

By

Roy Shadbolt

Introduction

Referred to as knife 'E' in the text, this seemingly unobtrusive First Pattern in rather poor condition turned out to be one of the most important discoveries in unlocking the story behind the very first production of First Pattern F-S Knives.

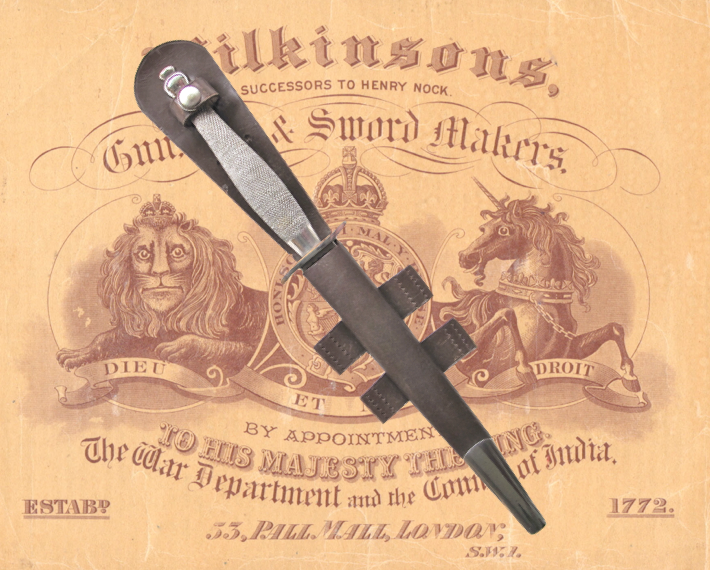

The Fairbairn-Sykes Fighting Knife needs little introduction. This iconic symbol of the British Commandos has now become inextricably linked with Special Forces the world over. The original ‘F-S’ Knife was of course manufactured by Wilkinson Sword Co Ltd of London, England, who would subsequently produce ‘three’ distinct versions or ‘patterns’.

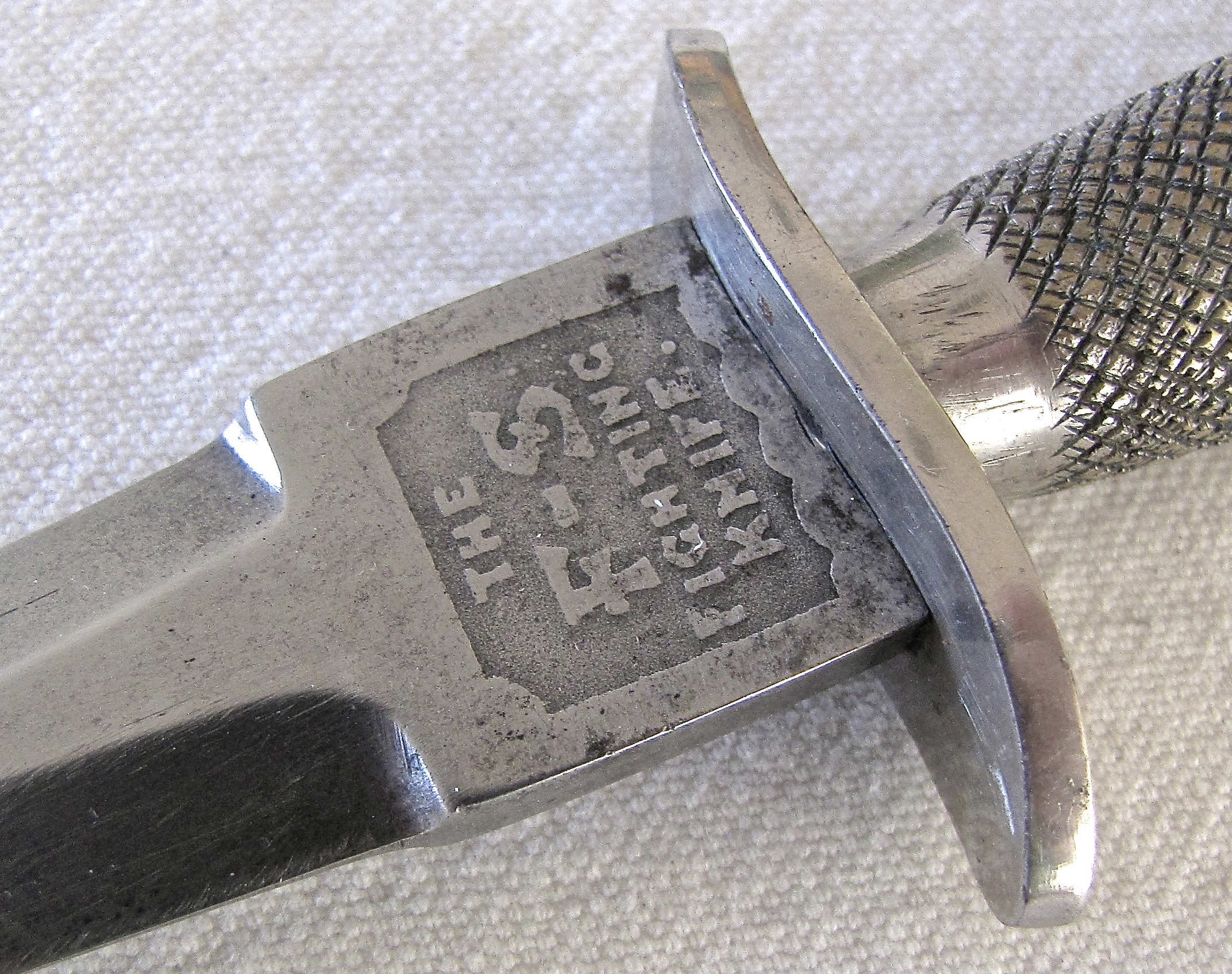

The first of these patterns is now referred to by collectors as (not surprisingly) the ‘First Pattern’. With its distinct etched square ‘tablet’ shaped ricasso and wavy ‘S’ shaped crossguard, it is easily distinguished from all subsequent patterns and variations.

Unlike the subsequent patterns that followed it, the First Pattern would for the most part remain very consistent in its design with very few production anomalies or manufacturing variations. As a result most First Pattern F-S knives are nearly identical to one another in somewhat of a ‘standardized’ pattern. There are of course a few exceptions to this; for example those knives that are stamped with the number 30946 (see the article 'The 30946 First Patterns') and those very few original examples known with a 3 inch long crossguard (see this article 'The 3 Inch Crossguard First Patterns') to name a few. But allowing for these singular anomalies, the rest of the knife still generally conforms to the ‘standard’ pattern having a commonality with most other First Pattern knives.

There is one very distinct variation of the First Pattern not previously recorded which, though incredibly rare, does consistently present a number of very interesting production differences to the standard pattern. It demonstrates what I believe are details that lend great weight to the hypothesis that these knives were produced in November of 1940 as part of the very first 'trials' or pre-production knives and prior to the standard production First Patterns that were introduced in late January 1941.

Presented here is my research with observations and subsequent conclusions arising from over two decades of study and after having the opportunity to personally examine more that one hundred original Wilkinson First Pattern F-S knives.

Historical Perspective

Knife 'A' one of five such knife that made up part of this research project. Exhibiting all the manufacturing details associated with the earliest produced First Patterns.

For those amongst us who are not overly familiar with the early F-S history, perhaps a short historical perspective is prudent at this juncture.

The Fairbairn-Sykes or ‘F-S’ Fighting Knife was conceived by William E. Fairbairn and Eric A. Sykes - two pioneers of unconventional warfare. Both Sykes and Fairbairn attended a meeting on the 4th November 1940 with the managing director of Wilkinson Sword Co Ltd, John Wilkinson-Latham. Also in attendance on that Monday at No53 Pall Mall S.W. London was Mr Charles Rose - Wilkinson’s engineering manager and head of the Experimental Workshop. Subsequently a design was agreed upon and production of what we now refer to as the ‘First Pattern’ (F-S) commenced.

Shortly after the initial meeting on 14th November 1940 the first confirmed official order for F-S knives was placed by Wilkinsons. Production of the First Pattern would remain constant well into the next year (1941) until the introduction of the Second Pattern on 12th August 1941. During this nine-month production run it is estimated that the total production figure for the First Pattern was under 7,000 units but with current recorded survival rates around 7% it is certainly possible that actual production figures may have been somewhat lower.

Manufacturing Basics

Although I have no personal experience in the manufacture of knives, I do come from a manufacturing background. Many of my younger years were spent in the cabinet-making industry in my home country of England where I held a variety of senior (shop floor) positions. I was often required to develop and subsequently introduce new products. Such tasks inevitably involved the ‘ironing out’ of specific manufacturing, assembling and/or finishing techniques which almost always took place on the initial production 'trials' run. It is all well and good making a sample or two but you really get to grips with what is involved when the first trials run of products makes their way through the manufacturing process. It is in this first run that one finds out what works, what doesn’t, which processes are taking too long and what areas need to be rethought or discarded altogether.

When developing and introducing a new product with multiple components, many different processes are required to produce the finished product. Inevitably, those products produced in the very first batch will show subtle differences to products produced at a later date after all of the ‘kinks’ have been ironed out, issues resolved and the production process streamlined and made more efficient. In the absence of documented evidence, this personal background in conjunction with a common sense, practical ‘nuts and bolts’ approach based on many years of observation of the actual knives themselves forms much of the reasoning behind my observations and conclusions.

Early First Patterns

In this image (knife 'D') the coarse knurling which also has more closely to the crossguard is evident.

As previously mentioned as part of my research I have been fortunate to have personally examined a great many original Wilkinson First Pattern F-S knives. Almost all of these knives are very consistent in their construction with only minor deviations due to hand-grinding and/or fitting. However I have (as of writing) identified five knives that consistently deviate from the standard pattern and with few exceptions all share identical production anomalies. This, I believe, singles these examples out as having been produced in the first 'trials' production run late in 1940. Henceforth I shall refer to these five examples as ‘A’ through ‘E’.

I conclude that these examples are early production knives based on the presence of a number of production anomalies which, in the main, would be more difficult and/or time-consuming to produce. In other words, as the initial production process moves forward one would not wish to make it more difficult or more time- consuming to produce an item. That would simply not make any sense at all as rather quite the reverse would be desired. Logic dictates that one would take any steps to ‘streamline’ the process and endeavor to make the production process quicker, more efficient and less time-consuming. This is the basic principle of good business in the manufacturing industry and as such, any knives that consistently demonstrate details which would clearly take longer and be more difficult to produce must therefore be earlier and not later in the production timeline.

Production Anomalies

Overall there are no less than five significant production anomalies that I have identified which differ from the standard (First) pattern of F-S Knife. Two of these, although interesting, are less significant so I will deal with them first. The other two details are very significant as they impact one another and form the core of my hypothesis. The fifth production detail - for reasons that will become apparent - has to date only been observed on one example (knife E). Nevertheless this intriguing, recently discovered detail gives us what is arguably the final piece of the puzzle!

Etching & Knurling

In this image of knife 'B' the more elaborate etching is evident. Thus far these etchings have only been observed on these early knives. Note too the corse knurling and how close it comes to the crossguard.

The first two and less significant production differences are the Wilkinson etching panel and the grip knurling. The former, when studied closely, is clearly different to the etchings found on all other First Pattern knives. Although the central logo remains the same, the foliate device both top and bottom is clearly different and appears slightly more ornate. Out of the five identified examples, four have this more ornate etching panel. This etching panel to date has only been noted on knives that exhibit the other production differences. On its own this different etching panel tells us little but when combined with the other production differences it becomes reasonably clear that the etching was modified slightly for all subsequent production of First Patterns. Although the reason why this should be the case is open to speculation, perhaps a slightly more simplified version was easier to apply on the knife’s small ricasso?

The second of these first two anomalies is in the knurling to the grip. This seems to differ in two ways to the standard pattern. First; it appears very coarse compared to most other standard pattern knives. Perhaps this is reflective of new tooling? The second detail is that it terminates much closer to the crossguard. No obvious explanation comes to mind for this detail other than perhaps the machine was adjusted or ‘re-set’ after the initial production run.

Exaggerated ‘S’ Crossguard

A first production knife shown at left compared to a later, more standard First Pattern knife at right. The difference in the 'S' guard is clear but more importantly the curved shoulder grind to the ricasso is quite distinct.

The ‘S’ shaped crossguard is one of the most distinctive features on the classical Wilkinson First Pattern F-S Fighting Knife and remained a constant standard feature on this pattern. I have, however, observed on a few occasions that the crossguard had been assembled incorrectly i.e. fitted the wrong way around. This is an interesting detail to look out for but I’m convinced is no more than just an oversight on the part of the assembler and of no particular interest in regards the topic of this article.

Our the five featured knives all exhibit a crossguard which is distinctly recognizable by its exaggerated or pronounced ‘S’ curvature in comparison to the standard ‘flatter’ ‘S’ shaped crossguard one normally sees. It could be argued that an exaggerated form may or may not take more effort to produce. However it is not the form alone that one needs to focus on but more so how it impacts the blade’s ricasso shoulder and the subsequent grinding needed to marry up these components.

The Shoulder Grind

If when looking at the standard First Pattern one looks very closely at the fit where the crossguard abuts the shoulder of the blade’s ricasso, it is clear that the shoulder is ground flat on both sides and perpendicular to the centre line of the blade. The shallow curves of the ‘S’ guard comfortably allow for this. With the curvature of the crossguard being for the most part restricted to its extremities, the bulk of the central portion of the crossguard remains relatively flat - resulting in a snug fit to the ricasso shoulder. When examining a standard pattern nest to one of the five examples under discussion the differences become self-evident.

Shown in more detail the exaggerated curvature of the crossguard along with the grinding of the ricasso shoulders to facilitate a flawless fit between the blade and guard.

In contrast our five featured knives exhibit a crossguard that is quite distinctly more curvaceous, with the form exhibiting a continuous curve throughout its entire length. As a result the ricasso must also be ground in an identical ’S’ form to fit the crossguard in order to avoid any unsightly gaps and to facilate a correct and proper fit during assembly.

Hand fitting each knife in this manner was nothing new for Wilkinsons, as they had been making fine ‘bespoke’ knives since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Producing such a ‘custom’ fit would not have been an issue for their highly skilled craftsmen. However the problem was not in their ability to accomplish this but in the extra time and effort it would take. With potential orders numbering in the thousands, clearly a better, more efficient way had to be found. And I believe the common sense solution was to simply construct the ‘S’ shaped crossguard with a more gentle curve that would fit up against a squared off ricasso shoulder; thus eliminating the hand grinding and fitting process altogether. This is precisely what we see on the standard pattern knife as discussed at the start of this chapter.

Part Numbering

At the start of this analysis I mentioned a fifth production anomaly found on knife ‘E’. It is this significantly important discovery that I wish to address here.

I had come into my possession a First Pattern F-S (knife E) which exhibited all the production anomalies previously discussed; indicating to me that this was an early knife. The condition of this example was really quite poor and the knife was subsequently sold to a long-time collector friend of mine. The new owner being a competent knife maker in his own right decided that this example would be a good candidate for a gentle restoration. This is where it gets really interesting! On carefully disassembling the knife it was discovered that each component part was numbered to one another. The blade’s tang, the grip and of course, the pronounced ‘S’ shaped crossguard were all stamped with an identifiable assembly number ‘4’ - a detail that to date has never before been recorded. Which of course is quite understandable as who (without good reason) is going to disassemble their treasured First Pattern?

Knife 'E' showing the tang stamped with the assembly part number '4'.

Knife 'E' showing the guard stamped with the assembly part number '4'.

Knife 'E' showing the grip stamped with the assembly part number '4'.

Now disassembled and when examined closely you can clearly see that both ricasso shoulders have been expertly ground to match the ‘S’ curve of the crossguard. Once again, examining the crossguard closely the assembly number ‘4’ is thoughtfully stamped where it would be hidden by the grip, as is the case with the grip itself.

Numbering component parts was a normal process in the manufacture of arms that required hand fitting. Historically this was especially true in the gun trade, as each item was hand fitted and after assembling in the white, all parts would then be disassembled and stamped with the same number before being sent off for finishing so when returned for final assembly, the correct parts would once again be reunited correctly. Wilkinsons had its origins as a fine London gunmaker, so this was a process that was no doubt most familiar to them.

Another example discovered after my initial research clearly shows there are more examples out there as yet to surface.

Discovering this numbered First Pattern was for me the final piece of the puzzle and proved beyond all reasonable doubt that knives in the initial production were all hand-fitted and as these examples show us, had parts that were numbered to one another. Such a procedure - along with all the other production processes discussed - I believe makes clear that these knives were more time consuming to produce than was thought necessary and as a result, the appropriate steps were taken to streamline production and make it more efficient.

Conclusion

Taking into account all production anomalies mentioned, most of which are time consuming from a production standpoint, it seems reasonable to me that these examples are representative of those knives produced early on and most likely were part of the very first 'trials' batch to be manufactured in the closing weeks of 1940.

Another view of the ricasso shoulder grind (knife 'A'). Note how precise and carefully the shoulder has been ground to exactly match the undulating curve of the crossguard.

Of course such a study is for the most part reliant on having enough suitable examples available for study. In this case as mentioned earlier, I have personally examined more than one hundred original Wilkinson First Pattern F-S knives - likely more than most collectors have seen or will ever see. Five of these have been of what I now refer to as the early production pattern and one of these has been disassembled to reveal the part numbers already discussed. More examples would of course be preferable, especially in regards the opportunity to examine which ones have assembly part numbers or not. But generally disassembling any original F-S would in most cases ruin its value. Such an action is almost never recommended, so please if you have an original First Pattern (or any other F-S for that matter) absolutely DO NOT take it apart.

Early production First Patterns are excessively rare and as mentioned I have now had only five examples come through my hands. Nevertheless they represent a fascinating footnote in the production of this iconic fighting knife and an elusive variation for the serious collector to seek out. I personally feel that whatever the condition, all First Patterns should be considered a treasured find. And if you are lucky enough to have an ‘Early Production’ example, then count yourself very fortunate indeed.

Update

Further research into those very few knives known with a 3 inch crossguard have raised the likelihood that these early 'trials' knives discussed in this article were likely originally fitted with the larger crossguard, this being subsequently replaced by the shorter one present on all those remaining knives. For further details I highly recommend you also read the dedicated article on that topic 'The 3 Inch Crossguard First Patterns'.

July 2022 Update

A further example has now been noted with the assembly number 62 (see images below). This would seem to indicated the at least 62 examples were produced in this first batch. Now that we have confirmation of this number of sixty two knives, it seems possibly that this first production number may have been 72 (six dozen) or 100, working on the theory that an even number may have been on the worksheet. Pure speculation on my part but it bears thinking.

November 2023 Update

A newly discovered and very rare numbered Wilkinson First Pattern. Along with the other examples shown in this article, each component is hand stamped with an individual ‘assembly’ number, in this case ‘69’, the highest yet recorded. As with the other examples, the usual ‘hand-fitted’ details are evident, such as: shaped ricasso shoulders, extra wavy crossguard, etching & knurling details.

It is possible that 144 knives were produced in this first batch, this number being ‘one gross’. Although this method of numbering has long fallen out of use, it was in common usage by Wilkinson during this time period. This is only speculation on my part but perhaps future discoveries will illuminate this fascinating topic further.

My sincere gratitude to Eric Lemmer for allowing me to share this rare example here.